Understanding Social Institutions Class 11 Sociology

| Table of contents |

|

| Introduction |

|

| Family, Marriage and Kinship |

|

| Work and Economic Life |

|

| Politics |

|

| Religion |

|

| Education |

|

| Important terms |

|

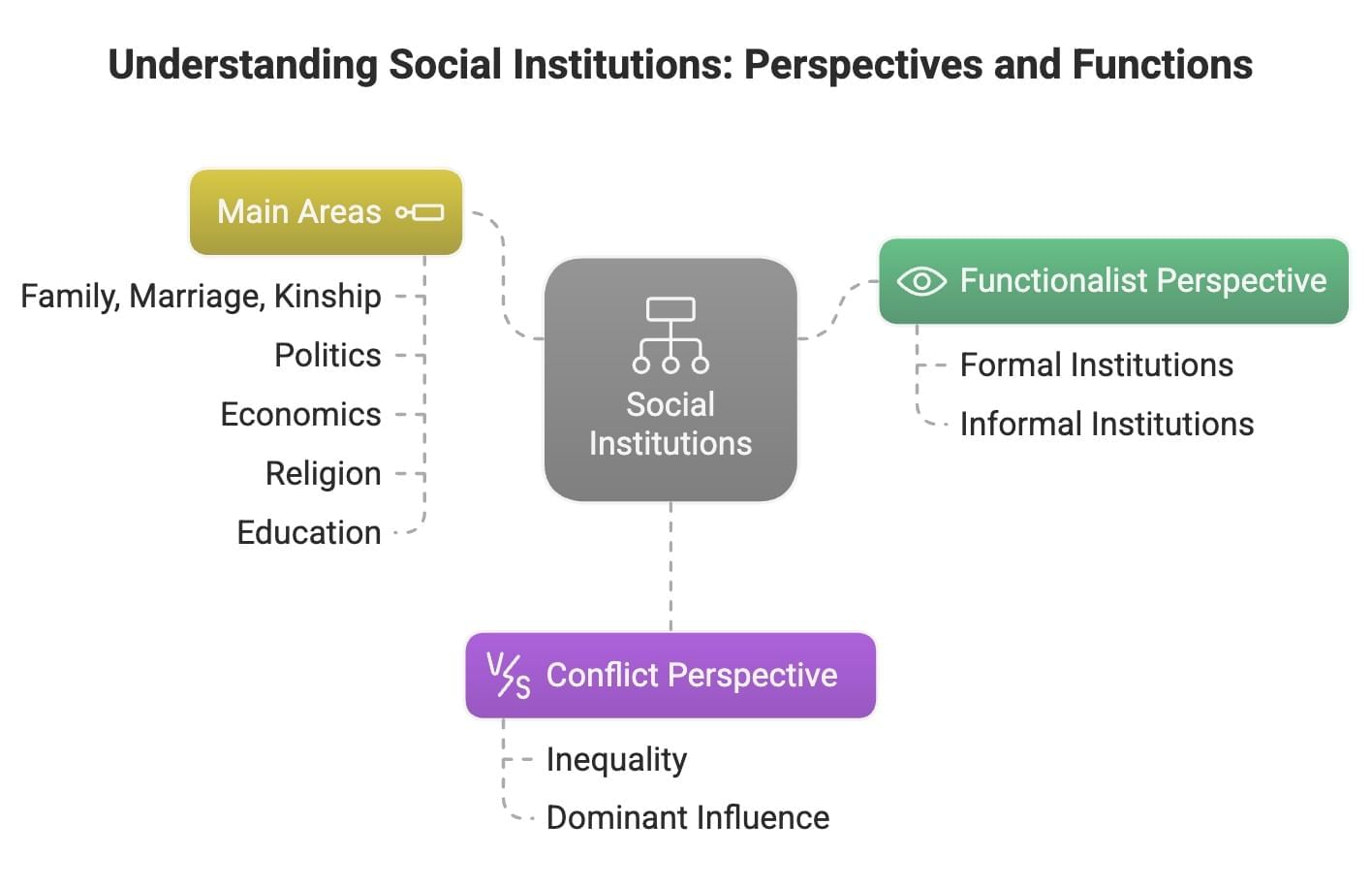

Introduction

Our status and role are predetermined and not subject to choice, unlike the roles an actor might play. Social institutions, including governmental and familial structures, impose limitations, punishments, and rewards on individuals. Sociology and anthropology examine these institutions, which are the focus of this chapter.

Institutions

An institution is an entity that functions according to established rules, whether these are legal or customary. Its regular functioning relies on following these principles, binding individuals to them. An institution can also be considered an end in itself, as people often view family, religion, state, or education this way.

For instance, family, church, state, and education are seen as both means to an end and as ends in themselves. The main areas where significant social institutions exist include: (i) family, marriage, and kinship; (ii) politics; (iii) economics; (iv) religion; and (v) education.

- Sociological Perspectives: Sociological interpretations of institutions vary. The functionalist and conflict perspectives offer different views on social phenomena such as stratification and social control.

Functionalist Perspective: From this view, social institutions are seen as complex systems of social norms, beliefs, values, and role relationships that emerge to meet societal needs. Societies have both formal and informal institutions. For instance, family and religion are considered informal social institutions, while law and education are formal social institutions.

Conflict Perspective: This perspective argues that not all individuals are treated equally in society. Social institutions—including family, religion, politics, economics, law, and education—serve the interests of dominant groups. The dominant sector influences political and economic institutions and ensures that the ruling class's beliefs become the prevailing ideas in society.

Family, Marriage and Kinship

A family is a group of individuals connected by blood, with adult members responsible for caring for children. Kinship links refer to relationships formed through marriage or bloodline that connect relatives.

Research on Family, Marriage, and Kinship: Sociology and social anthropology has conducted field research across various cultures to highlight the importance of family, marriage, and kinship institutions in all communities, though these institutions have different characteristics in different societies.

Functionalist Perspective: From this viewpoint, the family is crucial for fulfilling society’s basic needs and maintaining social order. Functionalists believe that modern industrial societies function best when women handle family care and men earn the family’s income.

Nuclear Family: Functionalists see the nuclear family as the ideal unit for industrial society. In this setup, one adult works outside the home while the other manages domestic tasks and child-rearing. The division of labour within the nuclear family typically involves:

- Husband: Taking on the "instrumental" role of breadwinner.

- Wife: Assuming the "affective" role, focusing on emotional care and domestic responsibilities.

Variation in Family Forms

- Shift in Family Structures: Sociologist A.M. Shah notes that since India's independence, the number of joint families has been growing. While nuclear families have always existed, they are more common among lower castes and classes.

- Increase in Joint Families: Shah attributes this rise to the increasing life expectancy in India. Life expectancy for men rose from 32.5 to 55.4 years, and for women, it increased from 31.7 to 55.7 years between 1941-50 and 1981-85.

- Impact of the Elderly Population: As a result, the percentage of elderly people (60 years and older) in the population has grown. Shah poses the question, "In what type of household do these elderly individuals reside?" He suggests that most live in joint households.

- Challenge to Common Views: This observation is a generalisation. However, it serves as a reminder to question the widely held belief that joint families are declining and highlights the necessity for thorough research and comparisons.

- Female-Headed Households: When men move to cities for work, women often take over farming and become the main earners for their families. These are known as female-headed households. This can also occur due to widowhood or when men remarry and stop providing for their former families. In the Kolam community, a tribal group in south-eastern Maharashtra and northern Andhra Pradesh, female-headed households are commonly accepted.

Matrilocal vs. Patrilocal Family Structures:

Matrilocal: Living with the wife’s parents.

Patrilocal: Living with the husband’s parents.- Patriarchal vs. Matriarchal Family Structures:

Patriarchal: Men hold authority.

Matriarchal: Women hold significant power, though true matriarchal societies are rare. Matrilineal Societies: These societies trace lineage through the mother, but genuine matriarchal societies are less common.

Families are Linked to Other Social Spheres and Families Change

- Family, household, and their structure are closely linked to economic and political spheres.

- German unification in the 1990s led to a decline in marriage due to the withdrawal of welfare schemes and protection for families.

- Economic insecurity post-unification influenced people to refuse marriage, illustrating unintended consequences.

- Family and kinship are subject to change due to macroeconomic processes, but the direction of change varies by country and region.

- Change does not mean the complete erosion of previous norms and structures; continuity and change can coexist.

How gendered is the family?

- The idea that a male child will provide for parents in their old age, while a female child will leave upon marriage, leads families to invest more in male children.

- Although female babies generally have a higher chance of survival, the rate of infant mortality for female children is still greater than that for males in younger age groups in India.

Family and kinship are influenced by larger economic changes, but the way these changes occur can vary greatly between different countries and regions. Both change and continuity can exist together.

The Institution of Marriage

- Historically, marriage has existed in a wide variety of forms across different societies.

- Marriage has been observed to perform differing functions in various contexts.

- The methods by which marriage partners are arranged exhibit a remarkable variety of modes and customs.

Forms of Marriage

Variety of Marriage Forms:

Marriage comes in different forms, depending on the number of partners involved and the rules about who can marry whom. The two main forms based on the number of partners are monogamy and polygamy.

1. Monogamy: This form of marriage limits individuals to one spouse at a time. Here, a man can have only one wife, and a woman can have only one husband.

2. Polygamy: In contrast, polygamy allows individuals to have multiple partners at once and includes:

- Polygyny: A system where one husband has several wives.

- Polyandry: A system where one wife has multiple husbands. Despite the allowance for polygamy, monogamy is more common in practice.

3. Serial Monogamy: This form permits individuals to remarry, usually after a spouse dies or after a divorce, but they cannot have more than one spouse at the same time. It is common for men to remarry after the death of a wife.

Widow Remarriage: Historically, widow remarriage faced restrictions, especially among upper-caste Hindus, and became a major issue during the reform movements of the 19th century. In contemporary India, nearly 10 per cent of all women and 55 per cent of women over fifty years old are widows.

Polyandry and Economic Conditions: Polyandry can develop as a response to difficult economic conditions where one man cannot support a wife and children adequately. Extreme poverty can also pressure a group to limit its population.

The Matter of Arranging Marriages: Rules and Prescriptions

Mate selection varies across communities, with some allowing individuals to freely choose their own partners, while others involve parents or relatives in making such decisions.Rules of Endogamy and Exogamy

- Restrictions on who can marry can be either subtle or explicit, depending on the society.

- Endogamy requires individuals to marry within a culturally defined group, such as a caste.

- Exogamy mandates that individuals marry outside of their group.

- Endogamy and exogamy are applied to kinship units like clan, caste, or racial, ethnic, or religious groups.

- In India, village exogamy is practised in some northern regions, where daughters are married into families from distant villages.

- Village exogamy facilitates the bride's adjustment into the new family and minimises interference from her natal kin.

- The geographical distance and patrilineal system in village exogamy reduce the frequency of visits from married daughters to their parents.

- The departure from the natal home is often depicted in folk songs, reflecting the emotional pain of separation.

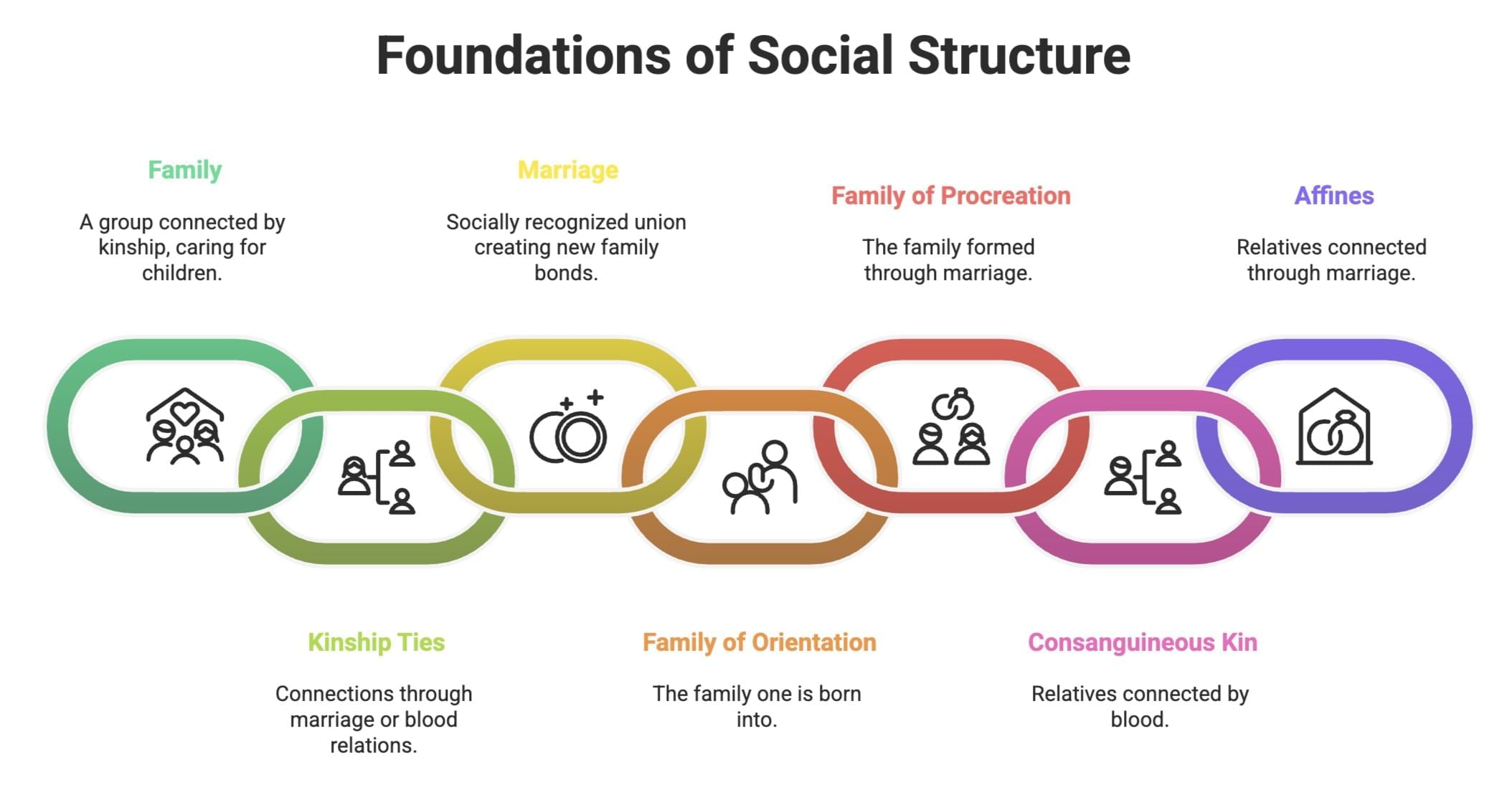

Defining Some Basic Concepts, Particularly Those of Family, Kinship and Marriage

- Family: A family is a group of people connected by kinship, where adult members take care of children.

- Kinship Ties: These are connections between people formed either by marriage or through blood relationships (like mothers, fathers, siblings, and children).

- Marriage: This is a socially recognised and accepted union between two adults. When individuals marry, they become relatives to each other, and this bond extends to their families, making parents, siblings, and other relatives related through the marriage.

- Family of Orientation: This refers to the family one is born into.

- Family of Procreation: This is the family formed when a person gets married.

- Types of Kin:

1. Consanguineous Kin: Relatives connected by blood.

2. Affines: Relatives connected through marriage.

Work and Economic Life

What is Work?

- Work is often thought of as paid employment when we are children and students.

- This is actually a simplified view.

- Many types of work, like those in the informal economy, are not counted in official employment statistics.

- The informal economy includes transactions that occur outside regular employment, often involving cash for services or the direct exchange of goods.

- Work can be described as the performance of tasks that require mental and physical effort, aimed at producing goods and services that meet human needs, whether they are paid or unpaid.

Modern Work Forms and Labour Division

Pre-Modern Societies: In pre-modern societies, most individuals worked in agriculture or animal husbandry. In countries like India, a significant portion of the population is still engaged in rural-based occupations and agriculture.

Modern Economic Systems: Modern economies are characterised by a complex division of labour. Work is divided into many specialised occupations, a stark contrast to traditional societies where non-agricultural work often involves a specific craft.

Work and Industrialisation: Before industrialisation, work was mainly conducted at home by all household members. The advent of industrial technology, such as coal-powered machines and electricity, led to a separation of work from the home. Industrial development centred around factories operated by capitalist entrepreneurs.

Specialised Employment: Individuals seeking employment in factories were trained to perform specialised tasks and were compensated accordingly. This specialisation is a key feature of modern society.

Economic Interdependence: Modern societies exhibit significant economic interdependence. With few exceptions, most people do not produce their own food, build their own homes, or make the goods they use.

Transformation of Work

- Mass production is dependent on the existence of mass markets. The development of the moving assembly line was one of the most important innovations in modern industrial production. This type of production required expensive equipment and continuous monitoring of employees using surveillance or monitoring systems.

- In recent decades, there has been a move towards what is known as "flexible production" and the "decentralisation of work." It is argued that in the era of globalisation, increasing competition between firms and countries necessitates the organisation of production to respond to changing market conditions.

Politics

Political Institutions: Political institutions handle the distribution of power within a society.

Power: Power is the ability of individuals or groups to achieve their goals despite opposition from others. It often means that those in power benefit at the expense of others. Power is relational, and the total amount of power in a society is fixed.

Authority: Authority is the use of power to enforce rules or make decisions. For instance, a school principal has the authority to enforce discipline, while a political party president has the authority to expel members. Authority is considered a legitimate and reasonable form of power and is often institutionalised based on this legitimacy. People respect those in authority because they believe their use of power is fair and just.

Stateless Societies

- Empirical studies of stateless societies by social anthropologists over sixty years ago showed how order is kept without modern government systems.

- Instead, there was a balance between different groups; alliances formed through family ties, marriage, and living arrangements; and ceremonies that included both friends and enemies.

- Rites and ceremonies that involve both friends and foes help maintain order.

- Modern states have a fixed structure and formal procedures. However, do some of the informal methods seen in stateless societies also exist in state societies?

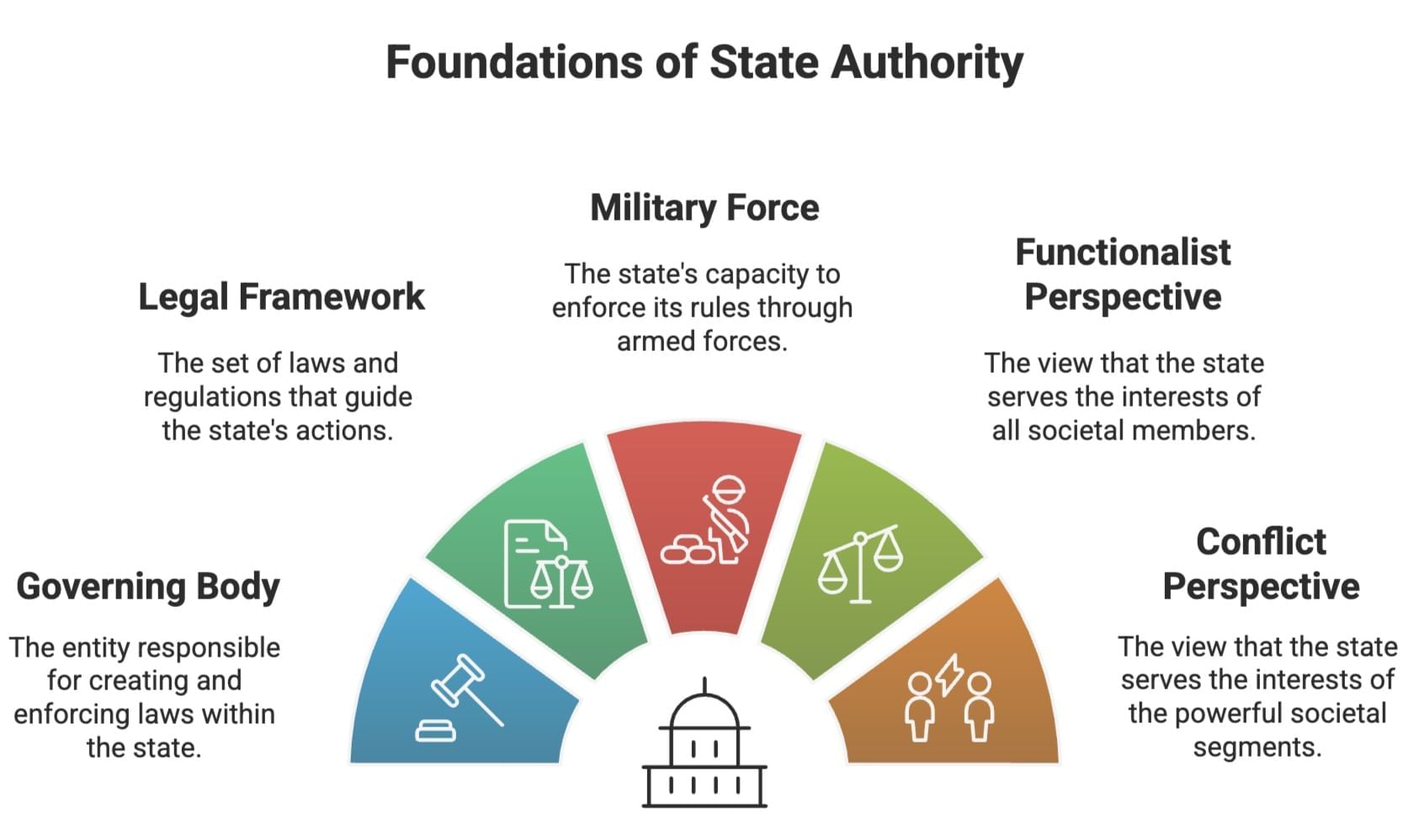

The Concept of the State

A state is defined as a political system with a governing body (such as a parliament or congress along with civil servants) that exercises authority over a specific area. This authority is supported by legal frameworks and the ability to use military force to enforce its rules.

Functionalist Perspective: This view holds that the state acts in the best interests of all parts of society.

Conflict Perspective: This perspective argues that the state serves the interests of the powerful segments of society.

Modern States:

Modern states differ significantly from traditional ones. They are characterised by sovereignty, citizenship, and often a strong sense of nationalism.

1. Sovereignty: Refers to the undisputed political rule over a territory.

2. Citizenship Rights: These rights include access to health services, unemployment benefits, and minimum wage standards. Initially, citizenship did not guarantee political rights. The expansion of social or welfare rights led to the creation of the welfare state in Western nations after the Second World War, though these are less common in developing countries and face challenges today.

- Civil Rights: These include freedoms related to movement, speech, religion, property, and justice.

- Political Rights: These pertain to the right to vote and hold public office.

- Social Rights: These encompass economic support, such as health care and minimum wage protections.

3. Nationalism: A sense of belonging to a political community (e.g., 'British' or 'Indian') that emerged with the modern state.

Contemporary Issues with States:

The contemporary world features rapid global market expansion and intense nationalist feelings and conflicts. Sociologists study the distribution of power not only in formal government but also across parties, classes, castes, and communities based on factors like race, language, and religion.

Religion

Study of Religion: Religion has long been a subject of study, with sociological findings often differing from religious reflections.

Sacred and Profane: Sociologists, following Emile Durkheim, study the sacred realm, which societies distinguish from the profane. The sacred often includes elements of the supernatural, though some religions (e.g., early Buddhism, Confucianism) may not conceive of the supernatural but still hold certain things as sacred.

Sociological Examination: Studying religion sociologically examines its relationship with other social institutions and its impact on power and politics.

Historical Movements: Historically, there have been religious movements for social change, addressing issues like caste and gender discrimination.

Public and Private: Religion is not only a private belief but also has a public character, affecting other societal institutions.

Secularisation: Classical sociologists believed that with modernisation, religion would become less influential, a process known as secularisation. However, contemporary events show that religion still plays a significant role, challenging the notion of secularisation.

Max Weber's Work: Max Weber's pioneering work links Calvinism to the rise of capitalism, showing religion’s influence on economic behaviour and investment.

Influences on Religion: Religious norms influence and are influenced by social forces such as politics, economics, and gender norms.

Women and Religion: The relationship between women and religion is an important sociological question.

Integration with Society: Religion integrates with other societal parts and plays a central role in traditional societies, often blending with material and artistic culture.

Sociological Methods: Sociology studies religion through empirical methods (observing actual functioning), comparative methods (comparing all societies), and by relating religious life to domestic, economic, and political life.

Common Characteristics: Religions share characteristics like symbols invoking reverence, rituals or ceremonies, and a community of believers. Rituals vary but often include praying, chanting, fasting, etc., and are distinct from everyday life. Religious ceremonies are practised collectively in sacred places like churches, mosques, temples, and shrines.

Sacred Realms: Sacred realms are approached with feelings of awe and respect, often involving specific rituals (e.g., covering one's head, and specific dress codes).

Education

Education is a lifelong process involving both formal and informal learning.

Here, the focus is on school education.

Admission to school is crucial for many, serving as a gateway to higher education, employment, and the acquisition of social skills.

Sociology views education as a transmission of group heritage, common to all societies, with distinctions between simple societies and complex, modern societies.

In simple societies, education was informal, with children learning customs and life skills through participation with adults.

Complex societies require formal education due to the economic division of labour, separation of work from home, and the need for specialised learning.

In modern societies, education is formal and explicit due to abstract universalistic values, as opposed to the particularistic values of simple societies.

Modern schools promote uniformity, standardised aspirations, and universalistic values. Examples include a uniform dress for school children.

Emile Durkheim argued that society needs a common base of ideas, sentiments, and practices that education must inculcate in all children, regardless of their social category.

Education prepares children for specific occupations and helps them internalise the core values of society. It maintains and renews the social structure and transmits culture.

According to functionalist sociologists, education also serves as a mechanism for the selection and allocation of individuals into future societal roles and statuses based on their abilities.

For sociologists who view society as unequally differentiated, education acts as a stratifying agent and reflects social stratification.

Educational opportunities vary based on socio-economic background, leading to differences in privileges and opportunities.

Privileged schooling can intensify the divide between the elite and the masses, affecting confidence and opportunities.

Many children cannot attend school or drop out, which perpetuates inequality in educational attainment and future opportunities.

Important terms

Citizen: An individual who is part of a political community, with both rights and responsibilities associated with that membership.

Division of Labour: The specialisation of work tasks where different occupations are integrated into a production system. While all societies have some form of division of labour, industrialism greatly enhances this complexity, making it international in scope in the modern world.

Gender: Socially defined expectations about appropriate behaviour for each sex, serving as a fundamental organising principle in society.

Empirical Investigation: The process of factual inquiry conducted within a specific area of sociological research.

Endogamy: The practice of marrying within a particular caste, class, or tribal group.

Exogamy: The practice of marrying outside a specific group of relations.

Ideology: Shared beliefs or ideas that justify the interests of dominant groups, prevalent in societies with systemic inequalities. Ideologies are linked with power, as they legitimise the unequal distribution of power among groups.

Legitimacy: The perception that a political system or order is just and valid.

Monogamy: A marital arrangement involving one husband and one wife exclusively.

Polygamy: A marital arrangement where an individual has more than one spouse simultaneously.

Polyandry: A form of polygamy where one woman is married to multiple men.

Polygyny: A form of polygamy where one man is married to multiple women.

Service Industries: Sectors focused on producing services rather than goods, such as the travel industry.

State Society: A society with a formal system of government institutions.

Stateless Society: A society without formal governmental institutions.

Social Mobility: The ability to move between different social statuses or occupations.

Sovereignty: The ultimate and uncontested political authority of a state over a defined territorial area.

|

41 videos|116 docs|17 tests

|

FAQs on Understanding Social Institutions Class 11 Sociology

| 1. What are the key social institutions discussed in the article? |  |

| 2. How do social institutions impact individuals and societies? |  |

| 3. What is the significance of understanding social institutions in humanities and arts? |  |

| 4. How do social institutions like family and education contribute to socialization? |  |

| 5. How do social institutions evolve and change over time? |  |