Class 7 Social Science Chapter 4 Let's Explore - New Beginnings: Cities and States

| Table of contents |

|

| Page 70: Think About It |

|

| Page 70: Janapadas and Mahajanapadas |

|

| Page 74: More Innovations |

|

| Page 76: The Varna-Jati System |

|

| Page 78: Think About It |

|

Page 70: Think About It

Q: Notice how many of the mahajanapadas are concentrated in the Ganga plains. There are several possible reasons for this, including the growth of agriculture in the fertile Ganga plains, the availability of iron ore in the mountains and hills (see below about iron), and the formation of new trade networks.

Ans: Reasons for Concentration in Ganga Plains:

- Fertile Agriculture: The Ganga plains, with their rich alluvial soil and reliable water from the Ganga and its tributaries, supported intensive agriculture. This surplus food production sustained larger populations and urban centers, fostering the growth of mahajanapadas like Magadha and Kosala.

- Iron Ore Availability: The nearby hills and mountains (e.g., in modern-day Jharkhand and Bihar) provided iron ore, which was critical for making tools and weapons. Iron technology, perfected by the late 2nd millennium BCE, enhanced agricultural productivity and military strength, aiding state formation.

- Trade Networks: The Ganga plains were a hub for trade routes like the Uttarapatha, connecting northwest to eastern India. This facilitated commerce, cultural exchange, and wealth accumulation, supporting urban growth in capitals like Rajagriha and Kausambi.

- Implications: These factors created a socio-economic environment conducive to the rise of powerful, urbanized mahajanapadas, marking the Second Urbanisation of India.

Fig. 4.2. The fertile Gangetic plains helped the mahājanapadas to grow and prosper.

Fig. 4.2. The fertile Gangetic plains helped the mahājanapadas to grow and prosper.

Page 70: Janapadas and Mahajanapadas

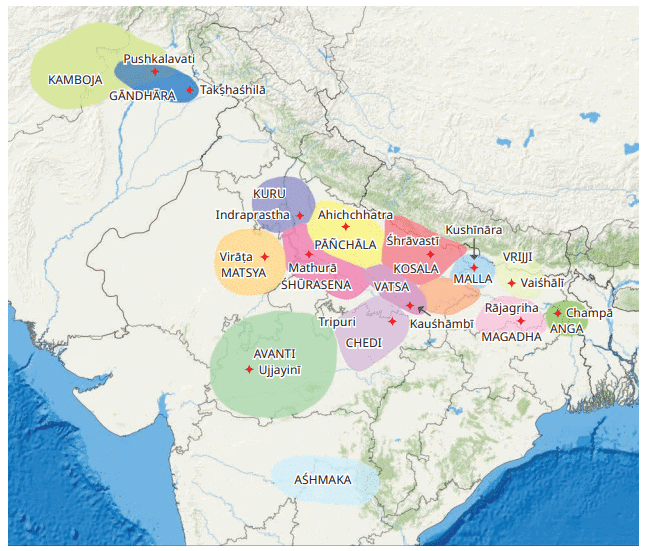

Q: The most powerful of these new states were Magadha, Kosala, Vatsa and Avanti. Looking at the map, can you identify their capitals? Also, how many can you match with Indian cities of today?

Ans: Capitals of Powerful Mahajanapadas:

- Magadha: Capital was Rajagriha (modern-day Rajgir, Bihar).

- Kosala: Capital was Sravasti (modern-day Shravasti, Uttar Pradesh).

- Vatsa: Capital was Kausambi (modern-day Kosambi, near Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh).

- Avanti: Capital was Ujjayini (modern-day Ujjain, Madhya Pradesh).

Matching with Modern Cities:

All four capitals match modern Indian cities:

- Rajagriha → Rajgir.

- Sravasti → Shravasti.

- Kausambi → Kosambi.

- Ujjayini → Ujjain.

Note: These ancient capitals remain significant cultural and historical sites, reflecting their enduring legacy from 2,500 years ago.

Q: Compare this map with the map of the regions mentioned in the Mahābhārata (see Fig. 5.4 in the chapter 'India, That Is Bharat' in Grade 6) and list the names common to both maps. What do you think this implies?

Ans: Common Names(assuming comparison with Mahābhārata map):

Likely common names between the mahajanapadas map (Fig. 4.3) and the Mahābhārata regions include: Fig. 4.3. Map of the sixteen mahājanapadas. Note that their borders are approximate.

Fig. 4.3. Map of the sixteen mahājanapadas. Note that their borders are approximate.

- Gandhara (northwest, modern-day Pakistan/Afghanistan).

- Kuru (northern India, near modern-day Haryana/Delhi).

- Panchala (northern India, near modern-day Uttar Pradesh).

- Kosala (eastern Uttar Pradesh).

- Magadha (modern-day Bihar).

- Anga (eastern India, near modern-day Bihar/Jharkhand).

Total Common Names: Approximately 6 (exact list depends on the Mahābhārata map, but these are frequently mentioned).

Implications:

- The overlap suggests historical continuity between the Vedic period (described in the Mahābhārata) and the mahajanapada era, indicating that these regions were significant cultural and political centers over centuries.

- It implies that the Mahābhārata reflects real geographical entities, blending mythology with historical reality, as these areas were key to India’s early state formation and cultural identity.

- The persistence of these names highlights the deep-rooted regional identities that shaped India’s political and social landscape.

Page 74: More Innovations

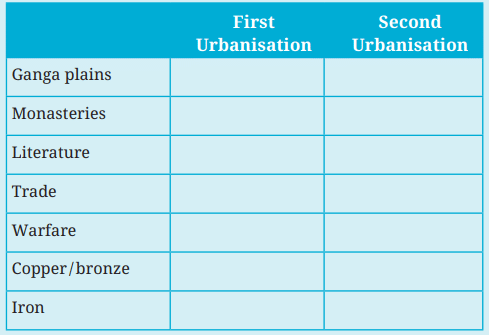

Q: Fill up the following table with a Yes (or tick mark) or No (or cross mark) in each square, which provides an interesting comparison between these two phases of Indian civilisation.

Ans: Completed Table(based on document content):

- Ganga Plains: First Urbanisation (Harappan, ~2000 BCE) was centered in the Indus/Sarasvati basins, not the Ganga plains (✗). Second Urbanisation (1st millennium BCE) flourished in the Ganga plains, e.g., Magadha (✓).

- Monasteries: Harappan civilization had no evidence of monasteries (✗). Second Urbanisation saw Buddhist and Jain monasteries emerge with new schools of thought (✓).

- Literature: No deciphered Harappan script exists, so no clear evidence of literature (✗). Second Urbanisation produced late Vedic, Buddhist, and Jain texts (✓).

- Trade: Harappan cities had extensive trade networks (✓). Second Urbanisation expanded trade with punch-marked coins and routes like Uttarapatha (✓).

- Warfare: Limited evidence of warfare in Harappan civilization (✗). Mahajanapadas engaged in warfare, using iron weapons (✓).

- Copper/Bronze: Harappans mastered copper/bronze metallurgy (✓). Second Urbanisation continued using these metals alongside iron (✓).

- Iron: Harappans did not use iron (✗). Iron tools and weapons were widespread in the Second Urbanisation, boosting agriculture and warfare (✓).

Page 76: The Varna-Jati System

Q: Why should a complex society divide itself into such groups? Think about several possible factors why this happens.

Ans: Reasons for Division into Groups:

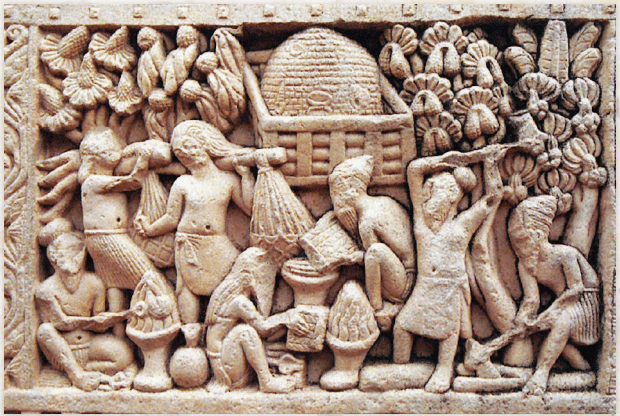

- Specialization: Complex societies require diverse skills (e.g., farming, metallurgy, governance). Dividing into groups like jātis (e.g., smiths, weavers) ensures efficient task allocation, as seen in the Sanchi stūpa panel (Fig. 4.5) depicting a smithy.

Fig. 4.5. A panel of the Sanchi stupa depicting a smithy (or metal workshop), where different workers bring firewood, water, stoke the fire, beat the iron, etc.

Fig. 4.5. A panel of the Sanchi stupa depicting a smithy (or metal workshop), where different workers bring firewood, water, stoke the fire, beat the iron, etc. - Economic Stability: Occupational groups ensure consistent production and trade. Vaishyas (traders, farmers) and Shudras (artisans) supported the economy, while Brahmins preserved knowledge, stabilizing society.

- Social Organization: Grouping by varna (Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, Shudras) or jāti provides structure, defining roles and responsibilities. This helped manage large populations in urban mahajanapadas.

- Cultural Continuity: Skills and traditions passed within jātis (e.g., metalworking) preserved cultural practices, like specific marriage customs, fostering group identity.

- Resource Allocation: Divisions ensured resources (e.g., land, tools) were distributed based on occupation, supporting the state’s needs, such as taxes for fortifications.

- Outcome: While functional, these divisions often led to inequalities, as some groups (e.g., Brahmins, Kshatriyas) gained more power, a trend that became rigid later.

Q: List other such professions you expect in a complex society of the 1st millennium BCE.

Ans: Professions in a 1st Millennium BCE Society:

- Potters: Crafted clay vessels for storage and trade, essential in urban households (evident in archaeological finds).

- Weavers: Produced textiles for clothing and trade, supporting markets in cities like Ujjayini.

- Carpenters: Built wooden structures, chariots, and tools, vital for urban infrastructure and transport.

- Merchants: Facilitated trade of goods (e.g., spices, gems) along routes like Dakshinapatha, using punch-marked coins.

- Scribes: Recorded transactions or religious texts, supporting administration and literacy in late Vedic/Buddhist contexts.

- Priests: Conducted rituals (e.g., Vedic sacrifices), a Brahmin role central to cultural life.

- Soldiers: Served in armies of mahajanapadas like Magadha, using iron weapons for defense or conquest.

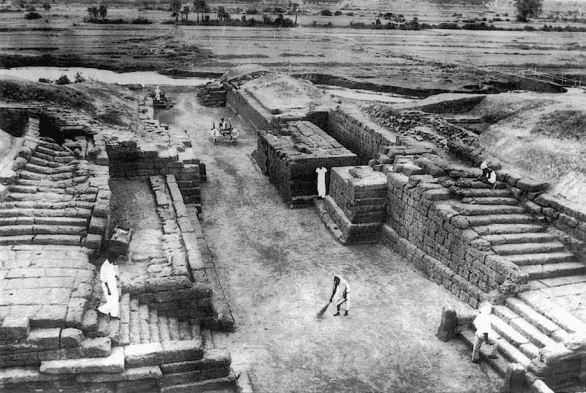

- Builders: Constructed fortifications, moats, and gateways (e.g., Shishupalgarh, Fig. 4.7).

Fig. 4.7: Shishupalgarh

Fig. 4.7: Shishupalgarh - Healers: Practiced early medicine, possibly Ayurveda, to maintain community health.

- Entertainers: Musicians or storytellers performed at assemblies or festivals, enriching cultural life.

- These professions reflect the diverse needs of urban mahajanapadas, supporting economic, cultural, and administrative functions.

Page 78: Think About It

Q: Inequalities within society can exist in many forms. Have you encountered any incident where you or anyone you know might have been made to feel different from others? Do you think equality is desirable in a society? If so, why? Have you come across people or initiatives that lessened inequalities?

Ans: Personal Reflection on Inequality(example response):

- Incident: I recall a classmate being excluded from a school event because their family could not afford the costume. They felt different and left out, highlighting how economic differences create social barriers.

- Desirability of Equality: Equality is desirable because it ensures fairness, allowing everyone to access opportunities (e.g., education, jobs) regardless of background. In the mahajanapadas, rigid varna-jāti systems led to discrimination against lower jātis, limiting their potential. Equality fosters social harmony, reduces conflict, and enables societies to benefit from diverse talents, as seen when individuals changed occupations.

- Initiatives to Lessen Inequalities: Programs like India’s Right to Education Act provide free schooling to underprivileged children, reducing educational disparities. Local NGOs often distribute food or skills training to marginalized communities, empowering them. Historically, Buddhist sanghas promoted equality by accepting members from all varnas, challenging social hierarchies.

- Connection to Text: The varna-jāti system’s flexibility in early periods allowed mobility (e.g., farmers becoming traders), but later rigidity caused inequalities, a lesson for modern societies to prioritize inclusivity.

|

23 videos|272 docs|12 tests

|

FAQs on Class 7 Social Science Chapter 4 Let's Explore - New Beginnings: Cities and States

| 1. What are Janapadas and Mahajanapadas? |  |

| 2. How did innovations contribute to the growth of cities and states in ancient India? |  |

| 3. What is the Varna-Jati system, and how did it influence society in ancient India? |  |

| 4. How did the emergence of states change the social and political landscape of ancient India? |  |

| 5. What role did trade play in the development of ancient Indian cities? |  |