Class 7 Social Science Chapter 5 Let's Explore - The Rise of Empires

Page 89: What is an Empire?

Q: Empires extended over vast areas and had diverse people with differing languages, customs and cultures. How do you think the emperors made sure that they lived in harmony? Discuss in groups and share your thoughts with the class.

Ans: Methods to Ensure Harmony:

- Inclusive Governance: Emperors like Aśhoka appointed officials to engage with diverse sects (e.g., Buddhists, Jains, Brahmins), as seen in his edicts, fostering mutual respect. Kautilya’s saptanga included councillors (amātya) to address local needs, ensuring fair administration across regions.

- Cultural Integration: Promoting shared values, like dharma, encouraged ethical conduct across communities. Aśhoka’s edicts in Prakrit, a widely understood language, communicated unifying messages.

- Infrastructure Support: Building rest houses, wells, and planting trees along trade routes facilitated interaction among diverse groups, fostering economic and social ties.

- Religious Tolerance: Aśhoka supported all sects, encouraging them to study each other’s teachings, which minimized religious tensions.

- Discussion Points: Groups might highlight how Aśhoka’s edicts promoted tolerance, or how trade guilds united diverse traders. Sharing with the class could involve a chart comparing methods (e.g., edicts vs. infrastructure) and their effectiveness in maintaining harmony.

Q: Looking at the many challenges involved in managing an empire, why should a king be so keen to expand his kingdom into an empire and become an emperor? Here are a few possible answers; see if you can think of a few more:

- An ambition to 'rule the entire world', a metaphor for controlling large territories and ensuring that they would be remembered for posterity;

- A wish to bring large areas under control and gain access to their resources to build economic and military strength;

- A desire for great wealth for himself and for the empire.

Ans: Additional Reasons for Expansion:

- Political Stability: Controlling vast territories reduced conflicts among smaller kingdoms, as seen in the Mauryan unification, creating a unified political structure under one ruler.

- Cultural Influence: Spreading the emperor’s ideology, like Aśhoka’s dharma, enhanced cultural dominance and legacy, influencing regions beyond India (e.g., Sri Lanka).

- Strategic Defense: A larger empire with fortified borders deterred external invasions, securing the core kingdom, as Chandragupta did against Greek satraps.

Fortified settlements would be built in strategic places, such as the empire’s borders.

Fortified settlements would be built in strategic places, such as the empire’s borders. - Trade Dominance: Controlling trade routes like Uttarapatha and Dakshinapatha (Page 93) ensured economic prosperity through taxes and access to diverse goods (e.g., silk, spices).

- Discussion: These reasons complement the provided ones, showing a mix of personal ambition (legacy), economic gain (trade, resources), and strategic goals (defense, stability). Students could debate which motive was most significant for rulers like Chandragupta or Aśhoka.

Page 91 & 93: Trade, trade routes and guilds

Q: Warfare apart, what other methods do you think the rulers might have used to expand their empires? Pen your ideas and share them with your class.

Ans: Non-Military Methods for Empire Expansion:

- Diplomacy and Alliances: Forming alliances with neighboring kingdoms, as Kautilya’s saptanga included mitra (allies), ensured peaceful integration. Chandragupta’s diplomatic ties with Greeks exemplify this.

- Marriage Alliances: Marrying into local royal families strengthened ties, ensuring loyalty without conquest, a common practice in ancient India.

- Economic Incentives: Offering trade privileges or tax exemptions attracted smaller kingdoms to join the empire, leveraging control over trade routes.

- Cultural Propagation: Spreading religious or philosophical ideas, like Aśhoka’s Buddhist emissaries to Sri Lanka, fostered cultural unity and voluntary submission.

- Infrastructure Development: Building roads, rest houses, and wells integrated regions economically and socially, encouraging allegiance to the empire.

Q: Observe the map of the trade routes. Identify geographical features that helped the traders travel across the Subcontinent.

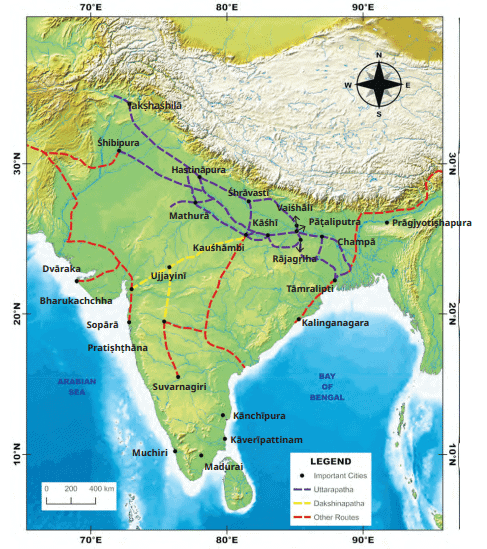

Ans: Geographical Features Aiding Trade Routes(based on Fig. 5.5): Fig. 5.5. Some important trade routes from about 500 BCE onward and major cities marked on them. Notice the Uttarapatha and the Dakṣhinapatha routes.

Fig. 5.5. Some important trade routes from about 500 BCE onward and major cities marked on them. Notice the Uttarapatha and the Dakṣhinapatha routes.

- Rivers: The Ganga and Son rivers facilitated trade in Magadha by providing navigable waterways for transporting goods like textiles and spices, reducing travel costs.

- Plains: The flat Ganga plains along the Uttarapatha route (northwest to eastern India) allowed easy movement of caravans and carts, connecting cities like Pataliputra and Taxila.

- Coastal Regions: Ports on the western and eastern coasts linked to routes like Dakshinapatha, enabling maritime trade with distant lands (e.g., Southeast Asia).

- Passes in Hills: Mountain passes in the northwest (e.g., Khyber Pass) along Uttarapatha connected India to Central Asia, aiding silk and gem trade.

- Forests and Hills: Provided resources like timber and herbs which traders accessed near routes, supporting local economies.

- Analysis: These features reduced travel barriers, ensured resource availability, and linked production centers (e.g., Magadha’s iron) to markets, making routes like Uttarapatha and Dakshinapatha vital for trade.

Q: What modes of transport on those roads do you think were available at the time?

Ans: Modes of Transport in 6th–2nd Century BCE:

- Bullock Carts: Used for carrying heavy goods (e.g., grains, textiles) along land routes like Uttarapatha and Dakshinapatha, suitable for flat plains.

- Horse-Drawn Chariots: Employed by traders and officials for faster travel, especially on well-maintained roads near cities like Pataliputra.

- Elephants: Used for transporting luxury items or in royal caravans, as they could navigate forests and hilly terrains.

- Boats and Rafts: Navigated rivers like the Ganga and Son for bulk goods, connecting inland cities to coastal ports.

- Pack Animals (Camels, Donkeys): Carried goods in arid or hilly regions, such as northwest routes to Central Asia, where camels were ideal.

- Foot Travel: Couriers and small-scale traders walked, carrying messages or light goods, as noted in city communication systems.

Page 94: The Rise of Magadha

Q: Take a close look at the panel given above. How many types of weapons can you identify? What different uses of iron can you make out?

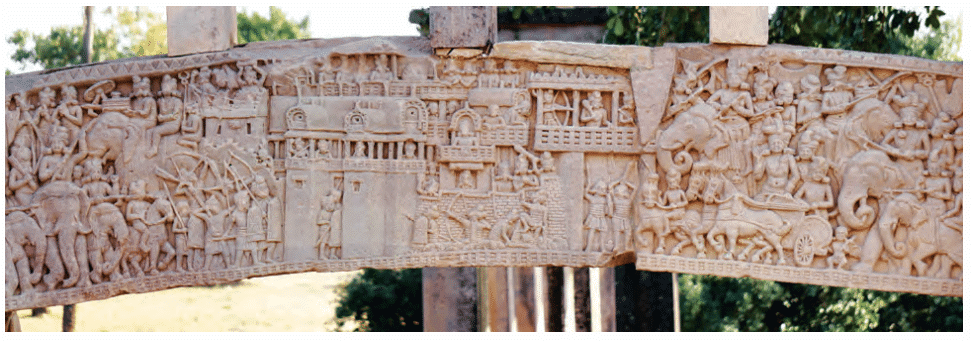

Ans: Analysis of Sanchi Stūpa Panel (Fig. 5.6, Page 94): Fig. 5.6. An elaborate panel from the Sanchi Stūpa depicting soldiers riding elephants, horses, or on foot, waging battle and laying siege to Kusinārā (today Kushinagar)

Fig. 5.6. An elaborate panel from the Sanchi Stūpa depicting soldiers riding elephants, horses, or on foot, waging battle and laying siege to Kusinārā (today Kushinagar)

Types of Weapons:

- Swords: Visible with soldiers on foot, used for close combat.

- Spears: Carried by some soldiers, likely for thrusting or throwing.

- Bows and Arrows: Archers are depicted, used for long-range attacks.

- Shields: Held by soldiers, for defense against enemy weapons.

- Total: At least 4 types (swords, spears, bows and arrows, shields).

Uses of Iron:

- Weapons: Swords, spearheads, and arrow tips were made of iron, valued for sharpness and durability, enhancing military strength (Page 94).

- Armor: Shields or body armor likely used iron reinforcements for better protection.

- Tools for Siege: Iron tools (e.g., axes, hammers) may have been used to breach fortifications during the siege of Kusinārā.

- Elephant/Horse Gear: Iron bits or fittings in bridles controlled animals in battle.

Q: In the left part of the panel, a parasol (chhattra) is kept over the casket containing the Buddha’s relics. Why do you think this was done?

Ans: Purpose of the Parasol (Chhattra):

- Symbol of Reverence: The parasol, a traditional symbol of royalty and divinity in ancient India, was placed over the Buddha’s relics to honor his spiritual authority, treating the relics as sacred, akin to a king or deity.

- Protection: It signified safeguarding the relics, both physically (from elements like sun or rain) and symbolically (as a mark of veneration during transport, as depicted in the panel).

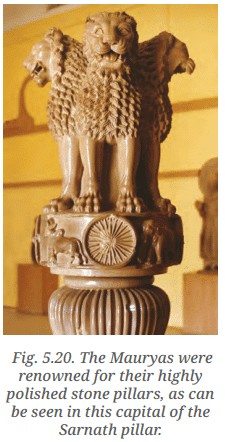

- Cultural Significance: Parasols were used in religious and royal contexts to denote high status, aligning with the Buddha’s revered position, as seen in Mauryan art like the Sarnath pillar.

- Context: The panel shows the relics being carried on an elephant, emphasizing their importance. The parasol underscores the Mauryan era’s respect for Buddhist relics, reflecting Aśhoka’s patronage.

Page 97: Think About It

Q: Why do you think Alexander wanted to rule over the entire world? What would he have gained from it?

Ans: Reasons for Alexander’s Ambition:

- Legacy and Fame: Alexander sought immortality through conquest, aiming to be remembered as a world ruler, as his push to the “end of the world” suggests a desire for a legendary legacy.

- Power and Control: Ruling vast territories granted supreme authority (imperium), consolidating military and political power, as seen in his defeat of Porus.

- Economic Wealth: Controlling trade routes (e.g., to India’s northwest) provided access to resources like gems and spices, enriching his empire.

- Cultural Exchange: Conquests facilitated blending Greek and local cultures (e.g., with Indian Gymnosophists), enhancing his reputation as a global unifier.

- Strategic Security: A vast empire deterred rivals, securing his homeland, though overextension led to fragility.

- Gains: He gained wealth, power, and a historical legacy, but his empire’s instability after his death shows the limits of such ambitions, mirroring the fragility of empires.

Q: When, after the battle, Alexander asked Porus how he wished to be treated, Porus answered, “Like a King.” Alexander then left Porus at the head of his kingdom, as satrap. With the help of your teachers, find more details on the battle between Porus and Alexander. Enact a play of this battle scene using your imagination in addition to what you have discovered.

Ans: Details on the Battle of Hydaspes (326 BCE):

- Context: Fought on the banks of the Hydaspes River (modern-day Jhelum, Punjab), Alexander’s Macedonian army faced Porus’s Paurava kingdom. Greek sources (e.g., Arrian’s Anabasis) describe a fierce battle.

- Key Events: Alexander crossed the river at night, surprising Porus. Despite Porus’s use of elephants, Alexander’s cavalry and phalanx outmaneuvered the Indian forces. Heavy rain made the terrain muddy, hindering Porus’s chariots.

A Greek coin probably showing Alexander on horseback attacking Porus on his elephant.

A Greek coin probably showing Alexander on horseback attacking Porus on his elephant. - Outcome: Alexander won, but impressed by Porus’s bravery, he asked, “How should I treat you?” Porus’s reply, “Like a King,” led Alexander to reinstate him as a satrap, ensuring loyalty without further conflict.

- Cultural Note: Greek accounts mention Indian women fighting alongside men, showcasing local resistance.

Play Enactment:

- Scene Setup: Stage a riverside battle with props for elephants (cardboard cutouts), horses, and a muddy field. Include a night crossing scene with Alexander’s troops.

- Characters: Alexander (confident leader), Porus (proud warrior), soldiers, and Indian women fighters. Add a Greek narrator (e.g., Megasthenes) for context.

- Dialogue: Highlight Porus’s defiance: “Treat me like a King!” and Alexander’s respect: “Your courage earns you your throne.” Include a Gymnosophist advising peace post-battle.

- Imagination: Add a scene where Porus’s warriors sing a war chant, or Alexander marvels at Indian elephants, emphasizing cultural contrasts.

Page 103: Think About It

Q: Kautilya says, “A king shall increase his power by promoting the welfare of his people, for power comes from the countryside which is the source of all economic activity. [The king] shall show special favours to those in the countryside who do things which benefit the people, such as building embankments or road bridges, beautifying villages, or helping to protect them.” Why do you think it was important to take special care of the countryside? (Hint: Think back to what you have learnt at the beginning of this chapter)

Ans: Importance of the Countryside:

- Economic Foundation: The countryside was the primary source of agricultural produce (e.g., grains), fueling the empire’s economy through taxes and trade. Surplus food supported urban artisans and armies, as seen in Magadha.

- Population Support: Most people lived in rural areas, providing labor for farming and resources like timber and elephants (Page 86). Neglecting them risked rebellion or economic collapse.

- Resource Access: Rural areas supplied raw materials (e.g., iron ore, herbs), critical for warfare and trade, strengthening the empire’s koșha (treasury).

- Stability and Loyalty: Infrastructure like embankments and bridges prevented famines and improved connectivity, ensuring rural loyalty to the emperor, vital for a vast empire.

- Link to Chapter Start: Kautilya’s quote, “There cannot be a country without people”, underscores that rural populations (janapada) were the empire’s backbone, sustaining its power and unity.

- Relevance: Prioritizing rural welfare ensured food security (e.g., Sohagaura granary) and economic stability, critical for maintaining an empire’s fragile structure.

Q: Organise a group discussion in your class and compare the features of Kautilya’s idea of an empire with a modern nation.

Ans: Comparison of Kautilya’s Empire and a Modern Nation:

Kautilya’s Empire (Saptanga):

- Swami (Ruler): The king, central to decision-making, prioritized subjects’ welfare. Example: Chandragupta’s leadership.

- Amātya (Ministers): Advised on governance, justice, and economics, ensuring efficient administration.

- Janapada (Territory/People): Rural-focused, with agriculture as the economic base.

- Durga (Fortifications): Protected cities like Pataliputra with moats and drawbridge.

- Koșha (Treasury): Funded through trade taxes and tribute, supporting armies and infrastructure.

- Danda (Army/Law): Maintained order and defense, using iron weapons.

- Mitra (Allies): Diplomatic ties (e.g., with Greeks) ensured peace and expansion.

- Philosophy: People-centric governance, with laws against corruption and focus on dharma.

Modern Nation (e.g., India):

- Leadership: Elected prime minister/president, accountable to citizens via democracy, unlike hereditary kings.

- Administration: Bureaucracy and ministries (e.g., Finance, Defense) parallel amātya, but with broader public participation.

- Territory/People: Includes urban and rural areas, with agriculture still vital but diversified economies (e.g., IT, industry).

- Defense: Modern military and police, akin to danda, use advanced technology, not iron weapons.

- Economy: Tax-based, with global trade, resembling koșha, but managed by central banks and policies.

- Infrastructure: Forts replaced by cybersecurity and borders, but roads/bridges remain key (like Kautilya’s rural focus).

- Allies: International alliances (e.g., UN, BRICS) mirror mitra, ensuring geopolitical stability.

- Philosophy: Constitution emphasizes justice, equality, and welfare, echoing Kautilya’s people-first approach but with secular governance.

Discussion Points:

- Similarities: Both prioritize welfare, economic stability, and strong administration. Kautilya’s anti-corruption laws align with modern anti-graft agencies.

- Differences: Modern nations use democratic elections, unlike monarchies, and have globalized economies versus regional trade (Page 91). Technology (e.g., digital governance) replaces manual systems.

- Activity: Divide class into groups to debate one saptanga element (e.g., koșha vs. modern taxes). Conclude with a chart comparing features, noting Kautilya’s enduring influence on governance.

Page 104: Think About It

Q: Ashoka, in his edicts, tells the story of the Kalinga war. He could have chosen not to mention it and maintain his image as a peaceful, benevolent king for future generations. Why do you think he admitted to this destructive war?

Ans: Reasons for Ashoka’s Admission:

- Transparency and Accountability: By admitting the Kalinga war’s devastation, Aśhoka demonstrated honesty, aligning with dharma’s emphasis on truth. This built trust with subjects, reinforcing his image as a reformed ruler.

- Moral Lesson: Publicizing his regret highlighted his transformation from violence to non-violence, encouraging others to follow Buddhist principles of peace, as seen in his emissaries to Sri Lanka.

- Political Strategy: Acknowledging the war contrasted his past aggression with his new benevolent policies (e.g., medical care, Page 106), strengthening his image as Devanampiya Piyadasi .

- Legacy Building: By documenting his change in edicts across the empire, Aśhoka ensured his story of redemption endured, influencing posterity.

- Impact: This openness made Aśhoka a “great communicator”, using edicts to project compassion, a model for modern leaders admitting past mistakes to inspire change.

Page 107 & 109: Life in the Mauryan period

Q: Aśhoka details instructions on the conduct of his officials and mentions ways to ensure that they practised fairness in one of his edicts. Read the translation below and share your thoughts on whether those ways would have been successful in helping manage his empire and how.

"By order of the Beloved of the Gods - the officers and city magistrates [...] are to be instructed thus: [...] You are in charge of many thousands of living beings. You should gain the affection of men. All men are my children, and just as I desire for my children that they should obtain welfare and happiness both in this world and the next, the same do I desire for all men. [...] You should strive to practice impartiality. [...] The root of all this is to be even-tempered and not rash in your work. [...] This inscription has been engraved here in order that the city magistrates should at all times see to it that men are never imprisoned or tortured without good reason. [...] And for this purpose, I shall send out on tour every five years, an officer who is not severe or harsh; who, having investigated this matter..., shall see that they carry out my instructions."

Ans: Effectiveness of Ashoka’s Methods:

- Gaining Affection: Treating subjects as “children” fostered trust, encouraging officials to prioritize welfare. This likely reduced local unrest, aiding empire stability, as happy subjects were less likely to rebel.

- Impartiality and Even-Temperedness: Promoting fairness and calm decision-making prevented biased judgments or harsh punishments, aligning with dharma. This ensured justice across diverse regions, strengthening administrative cohesion.

- Anti-Torture Measures: Prohibiting unjust imprisonment or torture protected citizens, enhancing Aśhoka’s benevolent image. This likely increased loyalty, crucial for managing a vast empire.

- Periodic Inspections: Sending non-harsh officers every five years to monitor magistrates ensured accountability, deterring corruption, a key Kautilyan principle. Regular checks maintained consistent governance across distant territories.

- Potential Challenges: Success depended on officers’ integrity and the empire’s communication network. Remote areas might have resisted inspections, and corrupt officials could evade scrutiny, a risk in large empires.

- Overall Impact: These methods likely succeeded by aligning governance with ethical principles, fostering trust, and ensuring oversight, though their effectiveness waned post-Aśhoka due to successors’ weaknesses. The edict’s public engraving ensured transparency, reinforcing compliance.

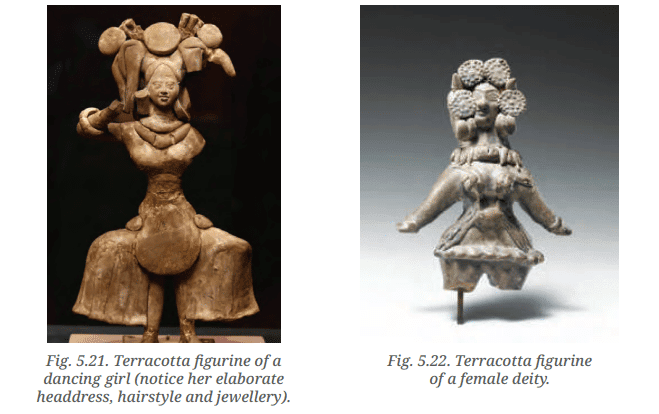

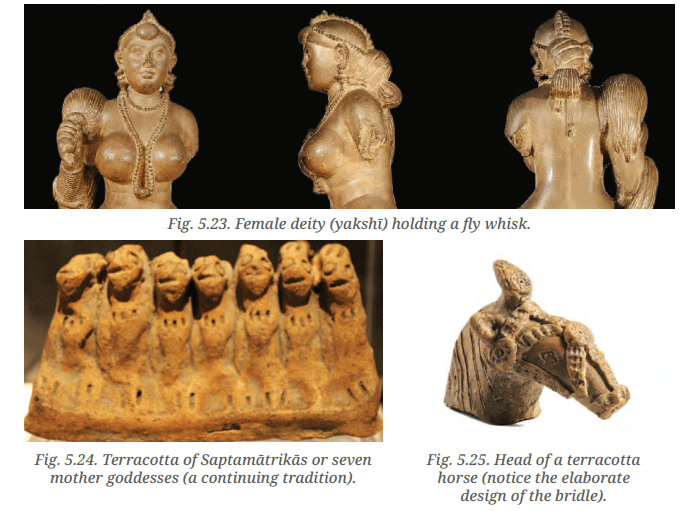

Q: Wear the hat of a historian. Look carefully at the artefacts presented on the spread on the next page. What conclusions can you draw about people and life during the Mauryan era?

Ans: Conclusions from Mauryan Artefacts (Figs. 5.20–5.27):

- Artistic Skill and Aesthetics: The Sarnath pillar capital (Fig. 5.20) and Sanchi Stūpa (Fig. 5.26) show advanced stone polishing and intricate carvings (lions, dharmachakra), indicating skilled artisans and a flourishing artistic culture patronized by rulers like Aśhoka.

- Religious Diversity: Terracotta figurines of deities (Figs. 5.22–5.24) and the Sanchi Stūpa reflect reverence for Buddhist and indigenous traditions (e.g., Saptamātrikās), suggesting a pluralistic society where multiple beliefs coexisted, supported by Aśhoka’s tolerance.

- Social Life and Fashion: The dancing girl figurine (Fig. 5.21) with elaborate headdress and jewelry, and descriptions of cotton garments, indicate a vibrant urban culture with attention to personal adornment, especially among women.

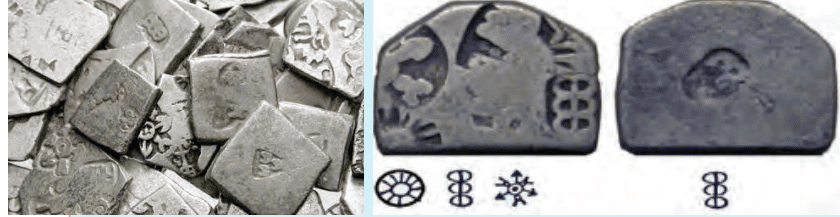

- Economic Prosperity: Punch-marked coins (Fig. 5.29) and trade goods (textiles, gems) point to a robust economy with standardized currency, supporting brisk trade via routes like Dakshinapatha.

- Urban Planning: Well-planned cities like Pataliputra with wooden houses, fire-prevention water vessels, and street signage suggest organized urban life, supported by a strong taxation system.

- Military and Animal Use: The terracotta horse head (Fig. 5.25) and Sanchi panel (Fig. 5.6) show elaborate bridles and elephant use, indicating advanced animal training for warfare and transport, vital for empire defense.

- Environmental Awareness: The Dhauli elephant sculpture (Fig. 5.27) and Aśhoka’s edicts on animal care suggest early conservation efforts, reflecting ethical governance.

- Overall Life: The Mauryan era was marked by urban sophistication, economic wealth, religious pluralism, and artistic excellence, driven by strong administration and trade, with Aśhoka’s policies fostering welfare and cultural unity.

Page 112: Some Contributions of the Mauryas

Q: Notice the different symbols on the coins. Can you guess what any of the symbols in the coins below might mean?

Ans: Symbols on Mauryan Punch-Marked Coins: Fig. 5.29.1. A hoard of Mauryan punch-marked coins, Fig. 5.29.2. A punch-marked coin of Aśhoka

Fig. 5.29.1. A hoard of Mauryan punch-marked coins, Fig. 5.29.2. A punch-marked coin of Aśhoka

- Sun Symbol: Likely represents divine authority or prosperity, common in ancient coinage to signify the ruler’s power, as seen in Aśhoka’s coins, aligning with his title Devanampiya.

- Crescent on Hill: May symbolize a sacred site or mountain, possibly linked to Buddhist or Vedic reverence for natural features, reflecting Mauryan religious patronage.

- Tree or Plant: Could denote fertility, agriculture, or dharma (e.g., Aśhoka’s tree-planting), emphasizing the empire’s economic and ethical foundations.

- Wheel (Dharmachakra): Represents Buddhist teachings, as seen on the Sarnath pillar, symbolizing Aśhoka’s commitment to dharma and moral governance.

- Animal Motifs (e.g., Elephant): Likely signify strength or royalty, as elephants were used in Mauryan armies and symbolized the Buddha.

- Interpretation: These symbols conveyed political legitimacy, religious values, and economic stability, reinforcing the ruler’s authority and the empire’s cultural identity. Their use on widely circulated coins ensured broad communication of Mauryan ideals.

|

23 videos|272 docs|12 tests

|