Legitimacy of the Judicial Branch Chapter Notes | AP U.S Government and Politics - Grade 12 PDF Download

Introduction

The judicial branch’s legitimacy hinges on the public’s confidence in its impartiality, autonomy, and fidelity to the U.S. Constitution. Unlike the legislative and executive branches, which wield control over financial resources and military force, the judiciary’s authority derives from its reputation, sound legal reasoning, and adherence to precedent. This legitimacy is not inherent but is earned through consistent application of the law, principled constitutional interpretation, and commitment to the rule of law.

Core constitutional provisions, such as Article III, and philosophical arguments, like those in Federalist No. 78, ensure the judiciary functions as an unbiased arbiter of the Constitution. The doctrine of stare decisis bolsters credibility by promoting continuity in legal rulings. However, the nomination of justices by presidents and their confirmation by the Senate introduces political and ideological influences, which can undermine perceptions of neutrality.

The Foundation of Judicial Legitimacy

Article III of the Constitution

Article III establishes the judicial branch as one of three coequal branches of the U.S. government. It creates the Supreme Court and empowers Congress to establish lower federal courts.

To safeguard judicial independence, it includes provisions that:

- Provide judges with lifetime tenure, contingent on maintaining “good behavior.”

- Prohibit reductions in judges’ salaries during their term of service.

These structural safeguards aim to insulate federal judges from political pressures, enabling them to base their rulings on legal principles rather than external influences.

Federalist No. 78 (Alexander Hamilton)

In Federalist No. 78, Alexander Hamilton defends the judiciary as the “least dangerous” branch, noting it lacks control over financial resources (Congress’s domain) or military power (the executive’s domain). Instead, its authority stems from its role in interpreting the Constitution.

Key arguments in Federalist No. 78 include:

- Judicial independence is essential, with protections to shield judges from political retribution.

- Courts are obligated to nullify legislative acts that violate the Constitution.

- Judicial review serves as a check to uphold constitutional limits, not as a means of asserting dominance.

Use on the AP Exam: Federalist No. 78 is frequently relevant for questions on judicial review, lifetime tenure, and the judiciary’s apolitical role. It pairs well with Marbury v. Madison or Supreme Court comparison free-response questions (FRQs).

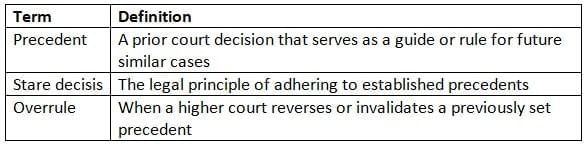

The Role of Precedent and Stare Decisis

Definition and Purpose

The doctrine of stare decisis, meaning “to stand by things decided” in Latin, dictates that courts should generally adhere to prior rulings (precedents) when deciding cases with similar facts. This principle is foundational to a stable and predictable legal system.

Why It Matters

The doctrine of stare decisis:

- Ensures predictability and uniformity in legal outcomes.

- Strengthens judicial legitimacy by preventing arbitrary or capricious rulings.

- Fosters public trust in the reliability of judicial decisions.

However, stare decisis is not absolute. Courts may overturn precedents deemed outdated, poorly reasoned, or unjust. The balance between upholding precedent and correcting past errors is a defining feature of U.S. constitutional law.

Judicial Flexibility: Adapting to Changing Times

While stare decisis promotes stability, the legal system must also adapt to societal changes. Courts occasionally reinterpret prior rulings to align with new realities, evolving values, or refined constitutional understandings.

Examples of Change

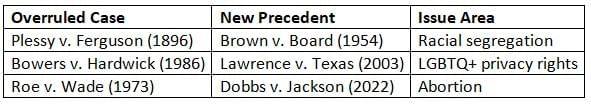

Brown v. Board of Education (1954) overturned Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), rejecting the “separate but equal” doctrine for racial segregation.

Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) expanded equal protection to recognize same-sex marriage, departing from earlier interpretations.

Why it matters: The Supreme Court’s legitimacy is not undermined by overturning precedent, provided the decision is supported by robust reasoning, transparent processes, and alignment with constitutional principles.

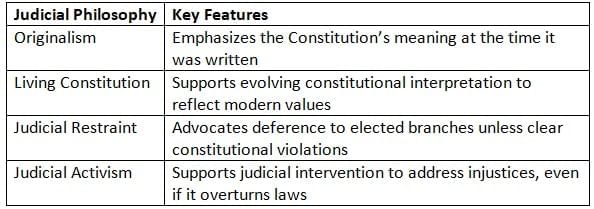

The Influence of Judicial Ideology

Judicial rulings are shaped not only by precedent but also by justices’ philosophical and ideological perspectives.

These perspectives influence views on:

- The approach to constitutional interpretation (originalism versus living constitutionalism).

- The judiciary’s role in safeguarding rights versus deferring to elected branches.

- The balance between federal and state authority.

Ideological shifts influence how closely courts adhere to precedent and whether they choose to uphold, limit, or reverse prior rulings.

Presidential Appointments and Shifting the Court

Given the lifetime tenure of Supreme Court justices, presidential appointments have a profound and enduring impact on the Court’s legal doctrines and ideological composition.

The Appointment Process

- Justices are nominated by the President.

- Nominations require Senate confirmation.

- The Constitution specifies no formal qualifications for justices.

Presidential appointments often reflect a desire to steer the Court’s ideological direction. Over time, these appointments can lead to the affirmation, reconsideration, or reversal of precedents, particularly in areas like civil rights, economic regulation, or federalism.

Why it matters: Appointments by presidents such as Franklin D. Roosevelt, Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush, and Donald Trump illustrate how presidents can shape the Court’s ideological trajectory for decades.

When the Court Overrules Itself

The Supreme Court rarely overturns its own precedents, but when it does, such decisions are typically grounded in strong constitutional reasoning.

Historical Examples of Overruling Precedent

Each instance reflects how new justices, shifting ideologies, and evolving societal norms can reshape legal precedents.

Conflicting Precedents and the Role of Lower Courts

Lower courts often encounter difficulties when interpreting or applying precedents, particularly when rulings from different appellate circuits conflict.

How Lower Courts Handle It

- Adhere to precedents set by the appellate court governing their jurisdiction.

- Distinguish cases based on factual differences when precedents are ambiguous or conflicting.

- In rare cases, defer or escalate cases to the Supreme Court for clarification.

This hierarchical structure ensures legal consistency while allowing flexibility in unique or unresolved cases.

Different Legal Systems: Is Stare Decisis Universal?

Common Law vs. Civil Law

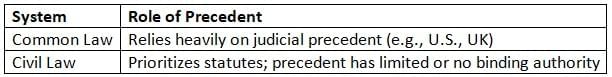

The U.S. operates under a common law system, which places significant emphasis on judicial precedent. However, not all legal systems treat prior rulings similarly.

In civil law systems, such as those in France or Germany, judges function more as investigators than interpreters, and prior rulings are not considered binding.

For AP Gov: Focus on the U.S. common law tradition and its connections to judicial review, Marbury v. Madison, and Article III.

Why It All Matters: Judicial Legitimacy on the AP Exam

Understanding judicial legitimacy involves recognizing how courts sustain public trust through:

- Adherence to precedent via stare decisis.

- Issuing rulings rooted in constitutional reasoning rather than political motives.

- Maintaining impartiality through lifetime tenure and appointment protections.

- Carefully reconsidering outdated precedents when justified.

On the AP Exam: Questions on judicial legitimacy often assess your grasp of:

- The balance between precedent and ideological shifts.

- The relevance of Federalist No. 78.

- The judicial structure under Article III.

- The impact of presidential appointments on the judiciary.

Key Terms

- Brown v. Board of Education: A pivotal 1954 Supreme Court case that declared public school segregation unconstitutional, overturning Plessy v. Ferguson and advancing the civil rights movement by rejecting the “separate but equal” doctrine.

- Civil Law Systems: Legal systems that prioritize written statutes and codes over judicial precedents, emphasizing codified laws and reducing the binding authority of prior rulings, as seen in countries like France and Germany.

- Common Law Systems: Legal frameworks that rely on court decisions and precedents as primary sources of law, fostering adaptability and legitimacy through judicial interpretations, as practiced in the U.S. and UK.

- Consistency: The practice of applying uniform rules and interpretations across cases, ensuring fairness and stability in the judicial system, which bolsters public confidence in legal outcomes.

- Ideology: A collection of beliefs and values that shape perspectives on governance and society, influencing judicial interpretations and the legitimacy of court decisions.

- Overrule: The act of a higher court nullifying a prior ruling, reinforcing the judiciary’s authority to ensure legal interpretations align with constitutional principles.

- Plessy v. Ferguson: An 1896 Supreme Court decision upholding racial segregation under the “separate but equal” doctrine, providing a legal basis for discrimination until overturned by Brown v. Board of Education.

- Predictability: The extent to which legal outcomes can be anticipated based on established precedents, enhancing public trust and ensuring fairness in the judicial process.

- Presidential Appointment: The President’s authority to nominate individuals, including federal judges, for key positions, subject to Senate confirmation, significantly shaping the judiciary’s ideological direction and legitimacy.

- Precedent: A legal principle established in a prior court case that guides future rulings, promoting consistency and predictability in the law and influencing governmental powers and rights.

- Stare Decisis: The legal doctrine of adhering to prior rulings, meaning “to stand by things decided,” which ensures stability and legitimacy in the judicial system by maintaining consistent legal interpretations.

FAQs on Legitimacy of the Judicial Branch Chapter Notes - AP U.S Government and Politics - Grade 12

| 1. What is the importance of legitimacy in the judicial branch? |  |

| 2. How does the concept of judicial review relate to the legitimacy of the judicial branch? |  |

| 3. What factors contribute to the perceived legitimacy of the judicial branch? |  |

| 4. How does public opinion influence the legitimacy of the judicial branch? |  |

| 5. What role does the Constitution play in establishing the legitimacy of the judicial branch? |  |